The crack cocaine surge that hit many U.S. inner-city neighborhoods in the mid-1980s was more than a drug trend; it was a shock to already fragile local economies and social networks. Because crack delivers a fast, intense high and is sold in small, frequent transactions, it fostered open-air markets that rewarded territorial control and rapid turnover. Where deindustrialization, redlining, and concentrated poverty had already narrowed opportunity, those markets drew in teenagers and young adults as sellers, lookouts, and enforcers, and violence quickly became part of the business model.

The health toll was multifaceted. Smoke inhalation damages the lungs; powerful stimulation strains the cardiovascular system; and, for pregnant users, there is elevated risk of miscarriage, low birth weight, and other complications that can affect an infant’s early development—effects made worse by poor access to prenatal care in many neighborhoods. Public-health summaries from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and clinical reviews detail these mechanisms and long-term risks.

Why did youth bear so much of the burden? Street-level crack dealing prized speed, mobility, and willingness to assume risk—traits often found among teens with limited legitimate job options. Credibility and protection were currency; guns were tools of both deterrence and status. Federal and state reports from the period describe how youth gangs, sometimes loosely organized and sometimes highly structured, intersected with drug markets. Scholars caution that not every gang was a disciplined trafficking enterprise; even so, the overlap between crack distribution and violent conflicts among groups is clear in the historical and criminological literature.

Crack, Couture, Concrete

Cocaine—and its cheaper, smokable offshoot, crack—didn’t just supercharge street economies in the 1980s and 1990s; it rewired aspiration and advertising. As cash churned, hip hop rose on radio and MTV, naming status objects in real time. Designer logos and badges—Gucci, Armani, Rolex, Mercedes-Benz—became narrative shorthand for survival and arrival, with measurable spikes in luxury name-drops across rap and R&B that functioned like free, high-frequency product placement. (FashionNetwork)

Harlem’s Dapper Dan embodied that exchange: he remixed European house codes into armored streetwear for rappers, athletes, and neighborhood kingpins, then—after years of legal pressure—returned as a celebrated collaborator, with Gucci backing a Harlem atelier and a co-branded collection. That arc from pariah to partner shows how street-level style unlocked new luxury customers while luxury, in turn, legitimized the very aesthetic it once shunned. (British Vogue)

Movies amplified the pull. Brian De Palma’s Scarface engrained a Miami-meets-opulence vocabulary—suits, watches, cars—that hip hop echoed for decades. Meanwhile, product placement research (from James Bond to broader film studies) demonstrated that on-screen integration boosts recall and desirability, reinforcing what videos and lyrics were already selling: luxury as evidence of power. (The Mob Museum)

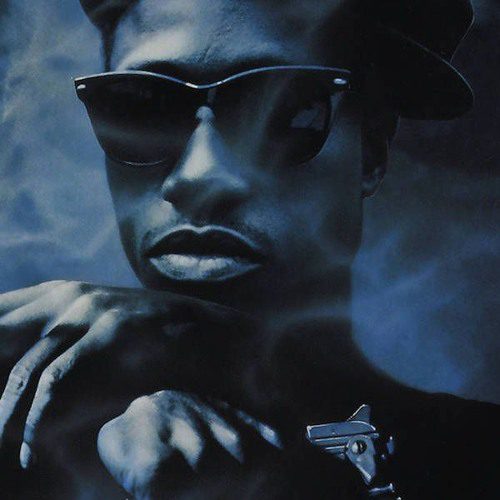

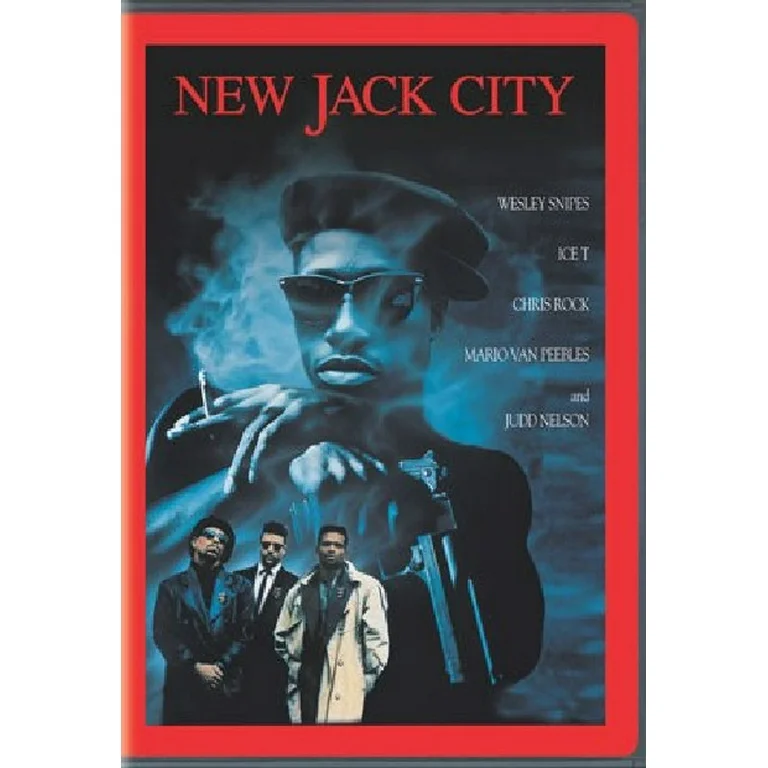

The film New Jack City Directed by Mario Van Pebbles follows Nino Brown’s rise as a ruthless crack kingpin, depicting cocaine’s corrosive pull on neighborhoods and aspirational lifestyles. The film fuses luxury fashion, nightclubs, and violent capitalism, showing how the crack economy financed status symbols, fractured communities, and shaped 1990s pop culture aesthetics, music, and urban ambition.

Miami turned that culture into concrete. The “Cocaine Cowboys” era coincided with fast-rising skylines; investigative reporting and law-review work describe how shell companies, cash purchases, and over/under-invoicing washed illicit proceeds into hotels, condos, and office towers. Recognizing the risk, the U.S. Treasury’s FinCEN imposed Geographic Targeting Orders to pierce real-estate secrecy—first in Manhattan and Miami-Dade, later across multiple metros—because all-cash, opaque deals are classic laundering vehicles. (The Guardian)

The loop worked like this: culture minted desire; artists and directors framed the goods with cinematic intention; luxury leaned in; and boom-town construction offered a ready sink for hot money. Time magazine was already documenting conspicuous narco purchases of prime South Florida property by 1981, a harbinger of cycles that would recur with each real-estate wave. Today’s compliance regimes are stricter, but the template—bling to billboard to building—still explains how crack-era cash cascaded from neighborhoods to malls to skylines across Miami and other U.S. cities. (TIME)

I

In short, hip hop’s storytelling didn’t merely reflect consumption; it created it. Luxury brands won new markets, films and videos magnified the message, and real estate converted liquid risk into tangible assets—crack, couture, and concrete bound together in one American business model. (FashionNetwork)

The violence did not disappear when the drug’s popularity faded. Newer work by Evans, Garthwaite, and Moore shows that in cities where crack markets emerged, murder rates for Black males ages 15–24 doubled soon after crack arrived and remained about 70% higher even 17 years later—evidence that guns and retaliatory norms seeded during the crack years created long-lasting risk environments for young men.

Criminal-justice responses left their own mark. Federal laws in 1986 and 1988 imposed severe penalties for crack relative to powder cocaine (a disparity later narrowed), which contributed to disproportionate incarceration of Black residents. That disrupted families and neighborhood institutions—churches, teams, block clubs—that typically help adolescents navigate away from the highest-risk paths. Meanwhile, aggressive policing often displaced street markets rather than eliminating them, pushing activity from one block to the next and reinforcing adversarial relationships between youth and authorities. (These dynamics are synthesized across the crack-impact literature cited above.)

Housing and neighborhood change complicated the story. As homicide rates fell in the mid-to-late 1990s and into the 2000s, investment returned to many once-stigmatized districts. In some places, reinvestment brought safer streets and new amenities; in others, it priced out long-time renters. Urban Institute researchers distinguish revitalization from gentrification and outline practical tools—tenant protections, inclusionary zoning, community land trusts, targeted repair grants—that can reduce displacement risks for low-income households while welcoming new capital. Evidence suggests renters face the most direct displacement pressure, while homeowners are less likely to move solely because of gentrification, especially where property-tax protections exist.

For youth growing up in places once dominated by crack markets, the legacy is mixed. On the positive side, national indicators show very low teen crack use today and far safer streets than the early 1990s. Yet the long shadow remains: peers and relatives carrying records that limit work and housing; wealth lost to foreclosures and incarceration; trauma from years when gunfire was common; schools and clinics stretched thin. Research on the enduring impact of the crack era’s gun diffusion helps explain why some cities still struggle with high homicide risks among young men despite progress elsewhere.

What works now is what always worked, but at scale and with staying power. Prevention and treatment on demand reduce demand-side harms; smart, focused deterrence shrinks the highest-risk networks without sweeping up entire neighborhoods; credible-messenger mentorship and trauma-informed schooling repair the social fabric for the next generation; and equitable development ensures that safety gains and new amenities accrue first to the residents who weathered the worst years. Gentrification does not have to mean displacement if cities plan up front with anti-displacement policies and resident ownership strategies.

The crack crisis was never just about a drug. It was about how a fast, cheap commodity exploited pre-existing structural weaknesses—job loss, segregation, underfunded services—and how policy choices amplified or softened the damage. Centering youth in the repair agenda is both a practical necessity and a moral one: they were the primary labor and the primary victims of the crack street economy, and they are the ones who will either inherit its aftershocks or build something sturdier in its place.

References

- Fryer, Heaton, Levitt & Murphy. Measuring the Impact of Crack Cocaine (NBER Working Paper 11318, 2005).

- Heaton, P. Measuring Crack Cocaine and Its Impact (article page).

- NIDA. “Cocaine” (health effects and risks).

- OJJDP. The Youth Gangs, Drugs, & Violence Connection (1999).

- Urban Institute. In the Face of Gentrification (report + strategies).

- Urban Displacement Project. “What are Gentrification and Displacement?” (research summary).

- Evans, Garthwaite & Moore. Guns and Violence: The Enduring Impact of Crack Cocaine Markets on Young Black Males (NBER/Kellogg/IPR summaries & paper).

- March of Dimes. “Cocaine and pregnancy.”

- (User preference) Harvard Book Store homepage.

- References

- Business of Fashion — How Hip-Hop Conquered Luxury High Fashion: (The Business of Fashion)

- FashionNetwork — Luxury brand mentions rise in music: (FashionNetwork)

- Fortune — Brands most mentioned in songs: (Fortune)

- Vogue — Gucci x Dapper Dan collection: (British Vogue)

- GQ — Dapper Dan on Gucci partnership: (GQ)

- The New Yorker — “Harlem Chic” (Dapper Dan, crack-era context): (The New Yorker)

- The Mob Museum — Scarface’s enduring cultural impact: (The Mob Museum)

- CrimeReads — Scarface as foundational hip-hop influence: (CrimeReads)

- HBR — The future of product placement: (Harvard Business Review)

- FinCEN — GTOs on Manhattan & Miami real estate: (FinCEN.gov)

- FinCEN — GTO renewal expanding to multiple cities: (FinCEN.gov)

- University of Miami Law Review — Miami real-estate laundering analysis: (Miami Law Repository)

- Time — “South Florida: Trouble in Paradise” (1981): (TIME)

- Harvard Book Store — Fashion Killa (contextual resource): (Harvard)